What 19th century stories can tell us about modern fish stocks

By Stephen Cain, RJD Intern

Shifting baselines, a term introduced by Daniel Pauly in 1995, occur when successive generations view contemporary environmental conditions as the baseline to measure future change against. The problem with this sort of bounded rationality is that it fails to account for long-term historic trends, and risks myopic decision-making in the greater context. This has been the error of monitoring global fish stocks. In 2001, Jeremy Jackson and several researchers suggested that humans began interacting in coastal ecosystems 10,000 years ago. However, developed nations only recently implemented monitoring fish stocks after the Second World War, with reliable reporting covering the last 40 years. Some of the more robust reporting involve economically important species, and often provide sparse information on non-target species. In the end, our understanding of virginal abundance, and the overall depletion of it, is piecemeal.

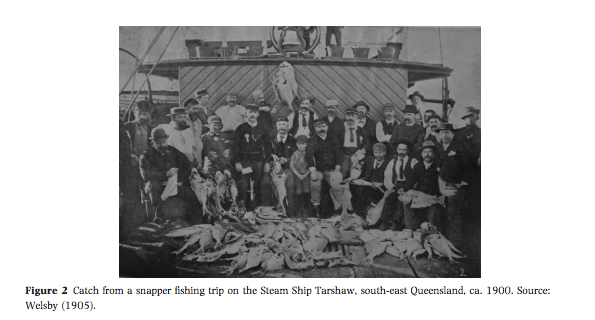

Enter Ruth Thurstan and researchers from The University of Queensland, in a partnership with the Australian government. In their recent study on the iconic Australian Snapper (Pagrus Auratus), Thurstan and her team examined two times sets of data: from 1879 to 1939 (development of the fishery), and 1940 to 2003. They devised a novel approach that has extended the baseline for the fishery back to the late 19th century. They argue that catch rates based on current fishing effort depict a fishery in decline since 1879. By their estimates, Snapper have declined by as much as 90%. Stable catch rates over time may have masked local declines as the fishery expanded its grounds and better technology became available.

Snapper are a species of bony fish that inhabit the rocky reefs of Eastern, Southern, and Western Australia. They range seas from New Zealand to Japan, and can live up to 30 years. In Eastern and Southern Australia, where the team collected data, the recreational Snapper fishery is estimated to be as much as 3 times larger than the commercial fishery. Because the relationship between Australians and Snapper goes back at least 130 years, the social and cultural context matters. According to Thurstan et al., while current gear, size, and allowable catch restrictions are in place, any future efforts to preserve the stock must exercise an understanding of the social ties to Snapper.

Historical ecology, or the study of ecosystems over time, is a discipline that has helped to address some of the issues of shifting baselines. As Thurstan et al. discuss, the trouble with examining their historical data, such as old newspapers, popular literature, and early scientific surveys, is that that information was incomplete, difficult to quantify, or suffered from reporting bias. On the other hand, they suggested that early data yielded qualitative insights that shaped assumptions about fishing effort over a longer time scale.

By piecing missing data together using relevant multiple imputation, the team generated catch rate data (derived from the number of fish, number of fishers, and time spent) that did not statistically differ from complete sources that allowed for cross-reference. The results were encouraging. By using narrative accounts of fish abundance, gear types, and information on the number of fishers of late 19th century recreational charters, Thurstan et al. were able to expand the data set to 278 entries. This is was a success considering that between all media only 47 records were replete with all 3 of the variables necessary for calculating fishing effort.

Snapper are considered data deficient according to the IUCN Red List. In Queensland, Australia they are considered overfished. The designation from the local governing body there has caused great public debate. As Australia’s governing bodies mull over how best to proceed, similar stories are unraveling worldwide. If the information we have available to us on fishery abundance is at best piecemeal, Thurstan et al.’s research breathes new hope into looking back so that we may go forward.

Nineteenth century narratives reveal historic catch rates for Australian snapper (Pagrus auratus) Ruth H Thurstan, Alexander B Campbell, & John M Pandolfi DOI: 10.1111/faf.12103

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!