Trade-offs Between Energy Maximization and Parental Care in a Central Place Forager, the Sea Otter

By Trish Albano, SRC Intern

Energy expenditure is a key component to consumer foraging strategies. In this study, the influence of prey availability and reproductive limitations were examined, in an effort to determine their impact on the foraging behavior of the southern sea otter (Enhydra lutris nereis). Theoretically, when food is plentiful, it is energetically efficient for a central place forager to exploit prey patches that are closest, therefore minimizing energy expenditure and conserving metabolic rate. The study predicts that as prey becomes more scarce, otters will dive deeper to find prey and the associated energy expenditure will be proportionately greater. Due to the physiological differences between males and females, the study predicts that males will show a greater range of dive depths and durations but both sexes will respond to prey scarcity in the same manner. The demands of pup care in females are also taken into account – it is hypothesized that if pup care plays a significant role in females’ diving behavior, mothers with small pups will stray from normal responses to food scarcity the most because deep, long dives could increase the likelihood of pup loss.

A mother and pup Southern Sea Otter (E. I. nereis). It has been shown that mother sea otters put a considerable amount of energy into the parental care of their pups. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Methods

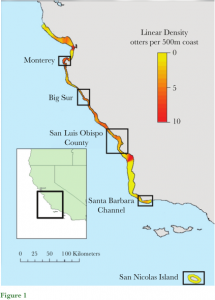

The researchers utilized TDRs (time-depth recorders) implanted in wild southern sea otters to collect data in 5 locations (Figure 1) (Monterey, Big Sur, San Luis Obispo County, Santa Barbara Channel, San Nicolas Island) along the California coast. TDRs stayed inside the animal for approximately 1 year. Most animals were observed from shore for behavioral data collection and it was noted that across all 5 sites, otters fed on 80 different species of benthic invertebrates. Both resource abundant (low otter density, high food density) and resource deficient (high otter density, low food density) sites were explored.

Figure 1: This figure shows the 5 sites that data was collected for Southern Sea Otter populations. In these locations, otters were fitted with TDRs and observed for study.

Results

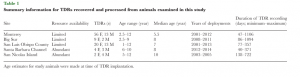

When prey was scarce, otters expanded their selection to include less-preferred prey. It was found that males and females without pups utilized similar foraging strategies and responses to food limitation, making deeper, longer and more energetically costly dives as prey became more scarce. However, females with pups were less likely to exhibit these energetically inefficient diving profiles. Mothers with young pups (less than 10 weeks old) placed parental care at higher priority than foraging when resource limitation would require them to perform energetically expensive dives that would reallocate their energy usage away from their pups. Females without pups in resource-abundant areas made 54% of dives to 2-5 m and 25% of dives to 6-10m whereas females with young pups made 3% of dives to 2-5 m, 52% of dives to 6-10 m, and 29% of dives to 11-15 m (Table 1). This trend of greater-proportion deeper dives was similar in resource-limited areas. This shows that females with pups utilized their energy in such a way that made it worth their while to leave their pups alone if there was a higher likelihood that they would be able to access food during their dive. Overall, the researchers’ hypotheses were supported by the data.

Table 1: This table shows the summary for TDRs that were used to obtain data in the study. The TDRs are site specific and measure resource availability, age range, median age, years of deployment, and duration of TDR recording.

Outcome

This study shows that prey availability is critical for all southern sea otters, but especially for mothers with pups. If resource abundance is depleted, it can become very risky and energetically expensive for otters to forage. This could cause an increase in pup mortality and become a threat to southern otter populations.

Resources

Thometz, N. M., et al. “Trade-offs between energy maximization and parental care in a central place forager, the sea otter.” Behavioral Ecology (2016): arw089.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!