Using Light to Reduce Sea Turtle Bycatch

By Emma Schillerstrom, SRC intern

We often hear about light pollution as a threat to sea turtle nesting success and hatchling survival. Artificial light near beaches discourages females from nesting, disorients hatchlings toward landing sites where they cannot survive, and can even increase the activity of predators that target their offspring (Silva et al., 2017) (Information About Sea Turtles: Threats from Artificial Lighting, n.d.). However, light may not be all bad for sea turtles. It could help them if employed as a method of bycatch reduction.

Bycatch, or the incidental capture of non-target species when fishing, is a threat to many marine animals (Henry, n.d.). Electric and magnetic devices have been studied as potential strategies to deter sharks from fishing equipment. They work by overstimulating their ampullae of Lorenzini – a sensory organ of jelly-filled pores which detect electrical impulses. Similarly, studies suggest fishers and managers may use light to protect sea turtles from fishing efforts.

Image of a sea turtle caught in fishery netting (Doug Helton, NOAA/NOS/ORR/ERD, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons).

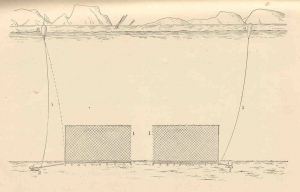

Bycatch reduction efforts for sea turtles have primarily focused on longlines and bottom trawls rather than set gillnets (Virgili, Vasapollo, & Lucchetti, 2018). TEDs, or turtle excluder devices, consist of a metal grid attached to trawl nets to physically block sea turtles from being able to enter the net, and NOAA has required them since 1987 for use by shrimp fisheries in the Gulf of Mexico and South Atlantic (Southeast Fisheries Science Center, 2019). While TEDs have been modified and improved over time, a similar device does not exist for gillnets.

Image of a turtle excluder device (William B. Folsom, NMFS (US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Drawing of a bottom set gillnet set-up (Joseph William Collins, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Using acoustic devices is not an effective strategy because sea turtle hearing is not sensitive enough for them to be selectively warded off (Virgili, Vasapollo, & Lucchetti, 2018). Visual deterrence, however, is much more promising since they rely heavily on visual cues for hunting, and bright light can be overstimulating (Virgili, Vasapollo, & Lucchetti, 2018). Chemical light sticks and LED lights have been tested in several studies and were found to be effective (Virgili, Vasapollo, & Lucchetti, 2018). Green, loggerhead, and leatherback sea turtles are sensitive to light in the ultraviolet (UV) range, whereas many commercially coveted fish are not (Wang, Barkan, Fisler, Godinez-Reyes, & Swimmer, 2013). UV-LED lamps are generally more expensive but have a longer life and greater light intensity, perhaps further lending to increased efficacy (Virgili, Vasapollo, & Lucchetti, 2018).

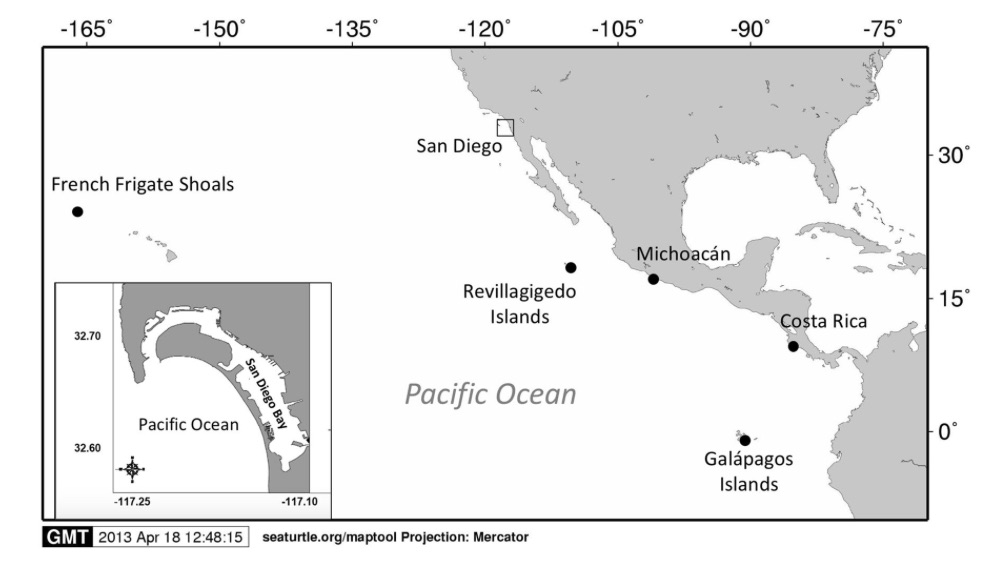

In a 2017 study, researchers at the CN-ISMAR Institute of Marine Sciences in Italy tested the ability of UV light to reduce loggerhead turtle bycatch in gillnets employed in the Mediterranean Sea (Virgili, Vasapollo, & Lucchetti, 2018). They modified nets by lining them with UV lamps spaced five and ten meters apart. By equipping some nets with lights and some without, they could compare the effectiveness of illumination for bycatch reduction through a measure called catch per unit effort, or CPUE. In this case, the catches were measured by weight or by the number of individuals, and the unit of fishing effort was standardized to be 1000 meters of net sitting underwater for 12 hours.

The addition of lamps led to a 100% decrease in bycatch. Sixteen loggerhead turtles were caught in control nets, while none were caught in the UV-lit nets. In this study, about 31% of the bycatch turtles were found dead, but in general, the mortality rate of sea turtles caught by gillnets may be as high as over 60% (Virgili, Vasapollo, & Lucchetti, 2018). All turtles caught were in nets at least 400 meters away from the illuminated nets. Between the control and illuminated nets, there was no significant difference in the CPUE in terms of the number or weight of animals caught once the bycaught turtles were excluded.

There was no observable effect of illumination on target catch efficiency, composition, or size of individuals (Virgili, Vasapollo, & Lucchetti, 2018). These findings suggest that the light did not affect the capture of target species, meaning fishery productivity should not be impacted by the addition of lamps to their nets. Based on optimized lamp spacing of 15 meters and an average net size of 300 meters, the cost of implementing this bycatch reduction device (BRD) would be around $6087 USD for an Italian vessel (Virgili, Vasapollo, & Lucchetti, 2018). A study in the Adriatic Sea in 2018 corroborated the effectiveness of this set-up, producing a 100% reduction in bycatch with two turtles caught in control nets among a mix of 20 illuminated and unaltered nets (Lucchetti, Bargione, Petetta, Vasapo, & Virgili, 2019).

In a 2013 study, researchers worked with volunteer commercial fisherman of a bottom-set gillnet fishery in Mexico (Wang, Barkan, Fisler, Godinez-Reyes, & Swimmer, 2013). They attached UV LEDs every five meters and turned them on in a subset of the nets. Fishery operations were carried out as usual. During the expedition, 332 green turtles were caught, with 209 caught in the control nets and 123 caught in the experimental nets, corresponding to a 39.7% reduction in the mean catch rate of the turtles. The scientists found no significant difference in target fish catch rates or the mean value per unit effort (VPUE) – bycatch profit – between the control and experimental nets (Wang, Barkan, Fisler, Godinez-Reyes, & Swimmer, 2013). The LEDs cost around $2 USD each, but a cost estimate for the whole fishery was not provided (Nuwer, 2013).

An alternate study conducted in northern Peru also tested green turtle bycatch reduction in gillnets (Ortiz et al., 2016). The CPUE of the turtles went down by 63.9% when illumination was added to the nets. Instead of UV light, they used standard LEDs, and the estimated costs for this set-up were 34 USD per turtle or 9200 USD for a whole gillnet fishery in Sechura Bay (Ortiz et al., 2016).

The current aim should be to optimize this bycatch reduction method by finding a balance between effectiveness and cost – in terms of device cost and any potential reductions in fishery catch – for realistic implementation. Currently, a great barrier to implementing light-based BRDs in fisheries appears to be their financial cost. However, TED use is nationally enforced offers hope that the regulated use of other bycatch reduction devices is possible and hopefully on the horizon.

Works Cited

Henry, L. (n.d.). What is bycatch? Understanding and Preventing Fishing Bycatch. (n.d.). Retrieved March 29, 2021, from https://www.worldwildlife.org/threats/bycatch

Information about sea turtles: Threats from artificial lighting. (n.d.). Retrieved March 29, 2021, from https://www.conserveturtles.org/information-sea-turtles-threats-artificial-lighting/

Keledjian, A., Brogan, G., Lowell, B., Warrenchuk, J., Enticknap, B., Chester, G., . . . Cano-Stocco, D. (2014). Wasted Catch: Unsolved Problems In US Fisheries. Oceana.

Lucchetti, A., Bargione, G., Petetta, A., Vasapo, C., & Virgili, M. (2019). Reducing Sea Turtle Bycatch in the Mediterranean Mixed Demersal Fisheries. Frontiers in Marine Science.

Nuwer, R. (2013, November 1). Ultraviolet Illumination Warns Sea Turtles away from Fishing Nets. Retrieved from Scientific American.

Ortiz, N., Mangel, J. C., Wang, J., Alfaro-Shigueto, J., Pingo, S., Jimenez, A., . . . Godley, B. J. (2016). Reducing green turtle bycatch in small-scale fisheries using illuminated gillnets: the cost of saving a sea turtle. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 251-259.

Silva, E., Marcob, A., Graça, J. d., Pérez, H., Abella, E., Patino-Martinez, J., . . . Almeidaa, C. (2017). Light pollution affects the nesting behavior of loggerhead turtles and predation risk of nests and hatchlings. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology, 240-249.

Southeast Fisheries Science Center. (2019, June 4). History of Turtle Excluder Devices. Retrieved from National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Virgili, M., Vasapollo, C., & Lucchetti, A. (2018). Can ultraviolet illumination reduce sea turtle bycatch in Mediterranean set net fisheries? Fisheries Research, 1-7.

Wang, J., Barkan, J., Fisler, S., Godinez-Reyes, C., & Swimmer, Y. (2013). Developing ultraviolet illumination of gillnets as a method to reduce sea turtle bycatch. Biology Letters.