FAD’s and Food Security in the Pacific Islands

By Kevin Reagan, SRC intern

In the countries and territories of the Pacific Islands, the people depend very heavily on fish for food. In Pacific Island countries and territories (PICT’s), 50-90% of the dietary animal protein in coastal communities comes from fish. This is based mostly on small-scale subsistence and commercial fishing for fish mainly associated with coral reefs, as well as some pelagic (open ocean) species (mainly tuna). Consumption of fish here is several times higher than the global average, and tuna is of particular importance and value (Bell et. al 2009).

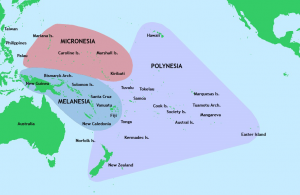

A map of the Pacific Island region. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pacific_Culture_Areas.jpg

As human populations grow, the government is encouraged to provide at least 35 kg of fish per person per year, due to the fact the fish is filled with fatty acids, proteins, and vitamins, and the most promising option for food security in the region. The arable, farmable land is scarce, which makes the level of subsistence provided from small farms scarce as well. It is also a better alternative to nutrient-poor imported foods that are beginning to be consumed in the region and can combat the occurrence of non-communicable diseases in the region (Bell et al. 2015).

The main issue currently is that coral reef fish populations cannot keep up with the growing demand for food, and will not yield the necessary 35 kg/person as the population continues to grow. Bell et. al (2015) propose that PICT’s allocate more of the tuna they catch to local food security, and make fish-aggregating devices (FAD’s) a priority. By 2035, it is estimate that tuna with need to account for 25% of the fish required for food security in the region (Bell et al. 2015).

A yellowfin tuna, the most common species of tuna caught in the Pacific Islands. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Al_mcglashan_tuna.jpg

FAD’s are though to be “one of the most practical vehicles for improving local fish access” in PICT’s (Bell et. al 2015), and are installed nearshore in depths of 300-700 meters. Pelagic fish tend to aggregate at and around floating objects for several days, and therefore FAD’s improve access to these fish. They have been shown to improve supply and consumption in rural areas, and cost-benefit analyses of FAD’s show the value of tuna and other pelagic fish exceeds the cost of the FAD by 3-7 times. The catch per unit effort tends to be higher, the average fuel consumption by the fisherman lower, and the returns on investment are anywhere form 80-180%. Preliminary studies in Micronesia and Vanuata indicate that FAD’s can alleviate fishing pressure on coral reef communities as much as 75% by transferring some of the fishing to oceanic fisheries, i.e. pelagic fish (Bell et al. 2015).

Though FAD’s have many benefits, extensive planning, monitoring, and research will be required for them all to be seen. An important aspect of this is participation and a sense of ownership by the local communities; some FAD’s have been sabotaged and vandalized in the past. Investments will need to be made, and are described in detail in the paper (Bell et al. 2015).

A fish-aggregating device (FAD) with mahi mahi schooling underneath. https://www.flickr.com/photos/landlearnnsw/3017619031

The first necessary investment is to identify priority locations for nearshore FAD’s. This is especially important in rural communities but is also important for urban communities. The community then needs to be engaged so that they can realize the full potential of FAD’s and none will be lost due to vandalism. The effectiveness of exclusion zones for industrial fleets must also be assisted; there are concerns that industrial fleets fishing near the boundaries of exclusion zones affect the number of fish that are then contained within the zone. Next, catches around nearshore FAD’s needs to be monitored and the level of improvement of coral reef management initiatives from FAD’s should be evaluated. Finally, the design and placement of the FAD’s must be improved (Bell et al. 2015).

FAD’s provide path to increase tuna and other pelagic fish availability to rural and urban comm. in Pacific Islands. They are a practical way to allow countries to get the small share of the region’s tuna catch they need to have food security, and are also a positive adaptation to climate change and population growth. Exclusion zone expansion needs to be considered as well if it is shown that industrial fleets are catching tuna marked in the exclusion zone (Bell et al. 2015).

Investments need to be made in FADs as part of food security in PICTs. Current FAD numbers not enough, and infrastructure needs to be maintained post-installation. Damaged FAD’s need to be replaced as soon as possible or momentum will be lost in the community. To do this, communities need large stockpiles of spare parts and access to the vessels and personnel necessary to install new FADs. However, current budgets are not large enough. National governments also need to be committed to and have ownership of FAD programs, and potentially use funds from license revenues from distant fishing nations that use their waters (Bell et al. 2015).

Local governments can also enlist the help of industrial fishing companies that currently deploy anchored FAD’s when fishing to assist in the installations of nearshore FAD’s. Each FAD program within PICT’s needs to be adapted to fit the capabilities of each particular island- the points outlined in paper are a blueprint, not a checklist. Overall, FAD’s are one of the few options that can provide food security, especially in rural coastal areas, and should be seriously considered in the coming years (Bell et al. 2015).

Works Cited

Bell, Johann D., et al. “Optimising the use of nearshore fish aggregating devices for food security in the Pacific Islands.” Marine Policy 56 (2015): 98-105.

Bell, Johann D., et al. “Planning the use of fish for food security in the Pacific.” Marine Policy 33.1 (2009): 64-76.