Albatross-born loggers show feeding on deep-sea squids: implications for the study of squid distributions

By Gaitlyn Malone, SRC intern

Deep-sea squids are considered to be an important prey source for many top marine predators including fish, marine mammals, and seabirds (Clarke, 1996). However, despite their importance in marine food web structures, there is relatively little known about the biology and ecology of these squids, due to lack of observations, as well as limited knowledge of when, where, and how top predators prey on them (Nishizawa et al., 2018). Albatrosses are just one seabird species that feed mainly on squid, including those deep-sea dwelling species. Since albatrosses feed by capturing prey on the surface of the water, how they are able to obtain deep-sea squid has long been a mystery.

Figure 1. Laysan albatross (Phoebastria immutabilis) near Kauai, Hawaii (Dick Daniels, Wikimedia)

Multiple methods for accessing these squid have been hypothesized including feeding on squid that are dead and floating after spawning, those discarded from fishing vessels and longliners, those regurgitated by cetaceans, those that are living and come to the surface at night, or those that are alive and aggregate at the surface near productive ocean fronts (Rodhouse et al., 1987; Thompson, 1992; Clarke et al. 1981; Imber, 1992; Xavier et al., 2004). A recent study examined the post-spawning floater, fishery-related, and oceanic front hypotheses using Laysan albatrosses that were breeding on Oahu, Hawaii (Nishizawa et al., 2018). Laysan albatrosses were determined to be a suitable species to test these hypotheses due to the fact that they feed on both on deep-sea dwelling squid species and Argentine squids (Illex argentines), which are often used as bait in the swordfish longline fishery in Hawaii. In order to perform this analysis, 38 birds that were raising chicks were fitted with GPS-loggers and camera-loggers during the early chick-rearing period in February and March of 2015. The GPS-loggers were positioned on the backs of the birds, while the camera-loggers were placed on either the back or the belly depending on whether the bird was brooding chicks. Images were only collected by the cameras during daylight hours and were used to identify any squid species the birds preyed on, whether those squid were alive or dead, and whether they were whole or fragmented. Camera images were also used to reveal if fishing vessels or cetaceans were present in the area.

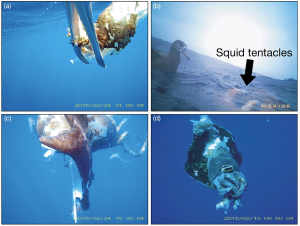

Figure 2. Images of squids recorded by the camera-loggers attached to Laysan albatrosses (Nishizawa et al., 2018)

In total, 26,068 images were obtained from 26 trips of 20 birds. Of those images, squids were visible in 23 images which corresponded to 16 predation events from 7 trips of 7 birds. Fishing vessels were found to be present in 69 images. All of the squids observed from the camera-loggers were dead and floating at the surface of the water, with ten of the squids being found in fragments while the other six were whole. Since many deep-sea dwelling squid species spawn and then die, it is possible that some of the squids present in the recorded predation events were the result of spawning mortalities. Although fishing vessels were observed, none were present in the images obtained during feeding events and the squids that were preyed upon were much larger than bait species. Therefore, these predation events are most likely not related to fishing occurring within the area. Overall, it was determined that Laysan albatrosses tend to feed opportunistically and do not tend to concentrate their efforts to a particular area. Through the use of GPS and camera-loggers, this study demonstrates how beneficial these devices can be in collecting information on the distribution of deep-sea squid and the significant role they play in the diet of marine predators.

Works Cited

Clarke, M.R. 1996. Cephalopods as prey. III. Cetaceans. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 351: 1053-1065.

Clarke, M.R., J.P. Croxall, P.A. Prince. 1981. Cephalopod remains in the regurgitations of the wandering albatross Diomedea exulas L at South Georgia. British Antarctic Survey Bulletin 54: 9-21.

Imber, M.J. 1992. Cephalopods eaten by wandering albatrosses (Diomedea exulans L.) breeding at six circumpolar localities. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 22(4): 243-263.

Nishizawa, B., T. Sugawara, L.C. Young, E.A. Vanderwerf, K. Yoda, Y. Watanuki. 2018. Albatross-born loggers show feeding on deep-sea squids: implications for the study of squid distributions. Marine Ecology Progress Series 592: 257-265.

Rodhouse, P.G., M.R. Clarke, A.W.A. Murray. 1987. Cephalopod prey of the wandering albatross Diomedea exulans.Marine Biology 96(1): 1-10.

Thompson, K.R. 1992. Quantitative analysis of the use of discards from squid trawlers by black-browed albatrosses Diomedea melanophris in the vicinity of the Falkland Islands. Ibis 134: 11-21.

Xavier, J.C., P.N. Trathan, J.P. Croxall, A.G. Wood, G. Podesta, P. Rodhouse. 2004. Foraging ecology and interactions with fisheries of wandering albatrosses (Diomedea exulans) breeding at South Georgia. Fisheries Oceanography 13(5): 324-344.