Rising Ocean CO2 Levels are Hurting Cephalopods

by Jessica Wingar, RJD intern

In the last decade, the concerns of how global climate change is going to affect our planet have grown. One of the main components of what is causing this climate change is the increase in carbon dioxide in our environment. There was a major increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere after the industrial revolution. The level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has risen from 280ppm to 390ppm. The carbon dioxide from the atmosphere diffuses into the ocean, which has created an increase in carbon dioxide in the ocean. With the increasing carbon dioxide levels in the ocean, the pH of the ocean will decrease leading to many detrimental effects on the animals that live there. It is predicted that by 2300 the carbon dioxide levels in the ocean will be around 1900 μAtm, which will cause the pH of the ocean to drop by 0.77. This decrease in pH will cause extreme changes in the ocean and how organisms develop and survive under these conditions is of utmost importance (Heuer, R., 2014). One of the many classes that has been studied is cephalopoda. The cephalopods include such animals as squid, cuttlefish, and octopus. They are a very important class to ocean trophic levels and to the economy and it is essential to determine what negative effects will occur to them in the coming years (Kaplan, M.B., 2013).

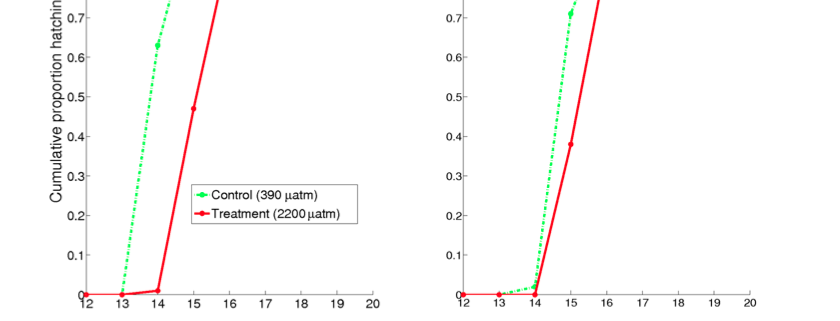

One of these economically important species is Doryteuthis pealeii, the longfin squid. Squid are a critical part of the food chain in the ocean because not only do they serve as prey for many organisms, such as tuna, but they also serve as predators of many organisms. In a study conducted in 2013, this certain species of squid was used. D. pealeii lives in shallow waters in coastal regions. In this study, individuals were taken from Vineyard Sound, Massachusetts on two separate occasions during their breeding seasons which lasts from May to August. The aim of this study was to calculate the difference in mantle size, statolith size, statolith characteristics, and hatching time between control embryos and embryos at an elevated carbon dioxide level of about 2200 μAtm. This is slightly above the predicted levels for the year 2300. The study found that in both trials, embryos hatched later in the carbon dioxide treatment than the control embryos. For example, in the first trial on the first day of hatching, 62.6% of embryos hatched, whereas only 0.7% of the embryos with increased carbon dioxide hatched. The negative effects of this delay may be that there is an increased chance for predation.

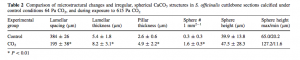

In addition to the hatching time, there were also many other negative changes in other parts of the squid. When the mantle length was looked at between the two conditions, the mantle was significantly shorter when the squid was reared in the carbon dioxide conditions. With a shorter mantle, the squid has less ability to move. Therefore, a shorter mantle can lead to slower swim speeds and lower migration causing a smaller chance of survival. Squid also have statoliths, which are calcified structures that are critical in balance and how the animal moves in the water. Seeing as these are calcified structures, their formation is greatly related to the acid content in the water. In this study, it was found that the statoliths of the squid in carbon dioxide had decreased surface area and a greater likelihood of abnormal shape and abnormal porosity. With decreased function of the statolith, the squid cannot orient itself the correct way in the water and again has decreased survival (Kaplan, M.B., 2013). Along with this type of cephalopod, cuttlefish also show a change in an inner calcareous structure in increased carbon dioxide conditions.

Some cuttlefish have a calcareous structure called a cuttlebone that is located dorsally that goes from just behind the head to the end of its body. The purpose of this bone deals with buoyancy. During the day, the chambers of the cuttlebone are filled with fluid, which make the cuttlefish able to sink, and at night this fluid is expelled, which causes the cuttlefish to stay in the same place in the water column. A study done on Sepia officinalis, the common cuttlefish, looked at morphological changes in the cuttlebone in a carbon dioxide rich environment. In this study they found that carbon dioxide exposed cuttlebones had significantly less height and length, but had a 20-55% increase in mass. The shorter height can be accounted for by the fact that the lamellae in the cuttlebone in the carbon dioxide treatment were a lot closer together, compacting the cuttlebone. In addition, the inner pillars of the cuttlebone were found to have doubled in thickness, showing a build up of carbonate and an increase in mass. A heavier cuttlebone is detrimental to a cuttlefish because in order for that structure to control buoyancy it needs to be as light as possible; the cuttlefish will not be easily able to move up the water column because it will take more work to make the animal neutrally or positively buoyant. In addition, it will be more difficult for the cuttlefish to maintain a position in the water column while hunting, which could cause starvation in the organism (Gutowska, M.A., 2010).

Research into the consequences of ocean acidification is increasingly necessary in order to determine what will happen to the ocean in the next few hundred years. The spike in the carbon dioxide content in the oceans has been directly caused my humans and it is imperative that now something is done to slow down this increase.

References

Gutowska, M.A., Melzner, F, Pörtner, H.O., and Sebastian Meier. (2010). Cuttlebone calcification increases during exposure to elevated seawater pCO2 in the cephalopod Sepia officinalis. Marine Biology, 157 (7): 1653-1663.

Heuer, R.M., and Martin Grosell. (2014). Physiological impacts of elevated carbon dioxide and ocean acidification on fish. American Journal of Physiology, 307 (9): R1061-R1084.

Kaplan, M.B., Mooney, T.A., McCorkle, D.C., and Anne L. Cohen. (2013). Adverse Effects of Ocean Acidification on Early Development of Squid (Doryteuthis pealeii). PLOS ONE, 8 (5): 1-10.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!