Overview

Overfishing is among the greatest threats facing marine biodiversity. Many species of top ocean predators, such as billfish, tunas and sharks, are experiencing unprecedented population declines worldwide. Sharks are among the most threatened marine animals worldwide. Recent estimates suggest that populations of many large sharks have declined by 90% or more in areas where they were once abundant. We are conducting a series of integrated field and laboratory studies in the Florida Keys to understand the ecosystem role of marine predators and the potential cascading effects of their declines on fish communities. This work will provide insights for predicting how both predators and prey are likely to respond to overfishing with implications for developing effective conservation and management strategies.

Recent Study Highlights & Selected Examples

Evidence from the wild as to the ecological and evolutionary consequences of top predator depletions remains limited, especially in marine systems. Given the pace and extent of predator loss, an understanding of these processes is important. Two sets of adjacent coral reef systems off north-western Australia have similar biological, physical and environmental conditions, but one of the reef systems has been exposed to nearly exclusive commercial fishing of sharks. In a new paper published in Marine Ecology Progress Series, our research team found that across reefs where sharks have been depleted, prey fishes had significantly smaller caudal fins and eyes compared to the reefs with intact shark populations (up to 40 and 46% relative difference in standardized means). These patterns were consistent across 7 teleost prey species (N = 611 individuals) that vary in behavior, diet and trophic guild. We hypothesize that these morphological patterns were primarily driven by differences in shark predation. Morphological differences were not consistent with plausible alternative explanations (habitat complexity, temperature, light, current, food availability, prey targets, competition) as primary drivers. These results provide field evidence of morphological changes in prey potentially due to predator depletions consistent with ecological predictions; specifically, predator loss caused a reduction in the size of prey morphological traits associated with predator detection and evasion. Our results indicate that predator removals may have profound effects on body shapes of prey communities. This is particularly significant in the case of sharks, given that the consequences of their widespread removal have been a topic of significant speculation, debate and concern. The differences in fish body shapes could have consequences for energy flow throughout the ecosystem, ultimately impacting the food web.

Hammerschlag N, Fallows C, Meÿer M, Seakamela SM, Orndorff S, Kirkman S, Kotze D, Creel S. (2022). Loss of an apex predator in the wild induces physiological and behavioural changes in prey. Biology Letters; 18: 20210476 https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsbl.2021.0476

Flecker AS, Twining CW, Schmitz OJ, Cooke SJ, Hammerschlag N. (2019) Aquatic Predators Influence Micronutrients: Important but Understudied. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.07.006

Hammerschlag N (2019). Quantifying shark predation effects on prey: dietary data limitations and study approaches. Endangered Species Research; 38: 147–151

Shiffman DS, Heithaus MR, Kaufman L, Hammerschlag N (2019). Intraspecific differences in relative isotopic niche area and overlap of co-occurring sharks. Aquatic Ecology; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10452-019-09685-5

Hammerschlag N, Schmitz OJ, Flecker AJ, Lafferty KD, Sih A, Atwood T, Gallagher AJ, Irschick DJ, Skubel R, Cooke SJ. (2019) Ecosystem Function and Services of Aquatic Predators in the Anthropocene. Trends in Ecology & Evolution; 34(4): 369-383.

Hammerschlag N, Barley SC, Irschick DJ, Meeuwig JJ, Nelson ER, Meekan MG (2018) Predator declines and morphological changes in prey: evidence from coral reefs depleted of sharks. Marine Ecology Progress Series 586:127-139.

Hammerschlag N, Meÿer M, Seakamela S M, Kirkman S, Fallows C, Creel S. (2017) Physiological stress responses to natural variation in predation risk: evidence from white sharks and seals. Ecology, 98: 3199–3210.

Hammerschlag N, Broderick AC, Coker JW, Coyne MS, Dodd M, Frick MG, Godfrey MH, Godley BJ, Griffin DB, Hartog K, Murphy SR, Murphy TM, Nelson ER, Williams KL, Witt MJ, Hawkes LA (2015). Evaluating the landscape of fear between apex predatory sharks and mobile sea turtles across a large dynamic seascape. Ecology, 96(8): 2117-2126.

Creel S, Becker M, Christianson D, Dröge E, Hammerschlag N, Haward MW, Karanth U, Loveridge A, Macdonald DW, Wigganson M, M’soka J, Murray D, Rosenblatt E, Schuette P. (2015) Questionable policy for large carnivore hunting. Science, 350(6267): 147-1475

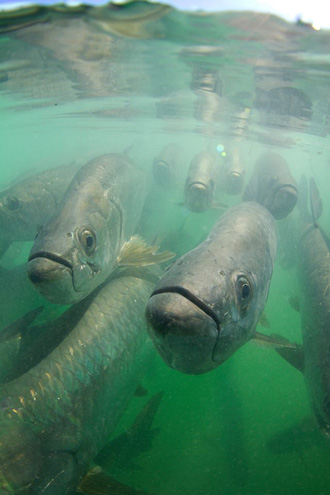

Hammerschlag N, Luo J, Irschick DJ, Ault JS (2012) A Comparison of Spatial and Movement Patterns between Sympatric Predators: Bull Sharks (Carcharhinus leucas) and Atlantic Tarpon (Megalops atlanticus). PLoS ONE 7(9): e45958. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045958

Hammerschlag N, Trussell G. 2011. Beyond the Body Count: Behavioral Downgrading of Planet Earth. Science. (E-Letter, 11 November 2011)

This project will increase our understanding of how predators can influence coral reef ecosystems. Such an understanding will aid scientists and managers in predicting how ecosystems may change following declines or recoveries of marine predators.

This project will increase our understanding of how predators can influence coral reef ecosystems. Such an understanding will aid scientists and managers in predicting how ecosystems may change following declines or recoveries of marine predators.