Decorating behavior begins immediately after metamorphosis in the decorator crab Oregonia gracilis

By Nicolas Lubitz, SRC intern

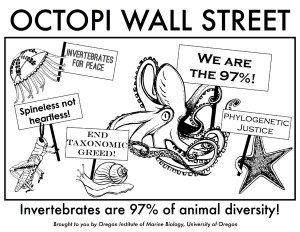

Invertebrates, animals without a backbone, are the oldest form of animals that exist on our planet. The first fossils of invertebrates date back to 665 million years ago, and are sponges. Since then, they have diversified into a spectacular array of organisms, both marine and terrestrial. From insects, to squids and corals, to jellyfish, their forms and shapes seem to know no limits. Some studies suggest that invertebrates make up 97% of all animal life on the face of the earth. For example, coral reefs provide shelter and structures for other organisms, most invertebrates are prey for higher organisms, but many invertebrates are predators themselves, like squid. With no doubt those creatures are vital to our marine and terrestrial ecosystems, and understanding their biology helps us to ultimately understand how every part of an ecosystem revolves around another part.

Figure 1. Invertebrate diversity (http://www.deepseanews.com/2011/11/octopi-wall-street/)

Because of the fantastic diversity of tasks they perform conserving invertebrate diversity is important to ocean health. Steven R. Hein and Molly W. Jacobs from the University of Washington and Miami University, respectively, have shown that there is even more to consider when looking at marine invertebrates. In their recent paper they looked at the decorator crab Oregonia gracilis (figure 1). Decorator crabs are known to use debris and other organisms such as sponges and algae to cover their outer layer, most likely for camouflage and protection. Just like other invertebrates of the order crustacea (which includes crabs and lobsters) decorator crabs go through different stages in their lives from larvae, to an intermediate phase, the so called megalopa, to a juvenile phase to the final adult stage. Each phase is very different in appearance and behavior. Hein and Jacobs were interested in how those different life stages utilize different habitats and different forms of debris and organisms to decorate themselves and how.

Figure 2. The decorator crab, Oregonia gracilis (http://www.crabs.ru/russia/fam_oregoniidae_oregonia_gracilis.htm)

In order to do so, they collected and bred different life stages of this particular decorator crab species and provided them with different decorating materials and habitats and compared the different stages for preferences. The results are clear: Although the early megalopa phases were found in mostly the same habitat as the juvenile phase, they did not decorate themselves at all. Juveniles, on the other side, utilized free floating organic debris to cover themselves which in turn is very different from adult individuals who use algae, sponges and other organisms. According to the researchers, the different body shapes of megalopae, juveniles, and adults requires all phases to adapt to different niches in order to survive.

When we look back to our idea of conservation we realize that when trying to come up with regulations and protective measurements for such organisms we should understand every single life stage of this particular organisms in order to ensure their conservation and protection. Hein and Jacobs indirectly demonstrated that laying out conservation measurements for just the adult phase appears to be insufficient since the whole life cycle has to be taken into consideration. Here we see that conservation is an integrative field and includes many components that we must look at for conserving our oceans.

Reference

Hein, S.R. & Jacobs, M.W. (2016) Decorating behavior begins immediately after metamorphosis in the decorator crab Oregonia gracilis. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 555, 141–150.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!