By Molly Rickles, SRC intern

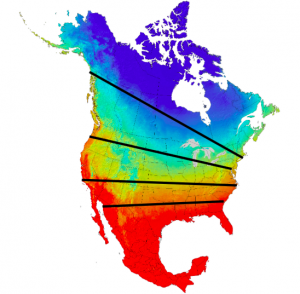

Coral reefs are dynamic ecosystems that harbor a quarter of all marine species while only occupying 0.2% of the world’s oceans (Chen, 2015). Coral Reefs are critical to the ocean’s health because of their biodiversity and complex ecosystems. However, climate change and anthropogenic disturbances has had a profound effect on coral reefs worldwide, with many reefs losing over 50% of their coral cover in the last 40 years (Baker, 2014). This is due largely to coral bleaching, a stress response induced by higher temperatures and excess nutrients. Bleaching is episodic, and the most severe events are coupled ocean-atmosphere events (CITE). Increased sea surface temperature causes coral cover to decrease when the temperature is higher than 26.85 degrees Celsius (Chen, 2015). Coral bleaching causes an increase in coral diseases as well as loss of habitat for many marine species. This eventually leads to a decrease in coral cover, which can disrupt the marine ecosystem and negatively impact the environment.

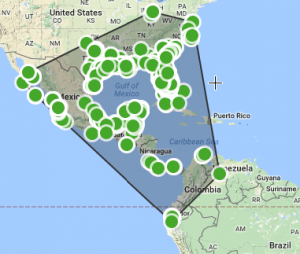

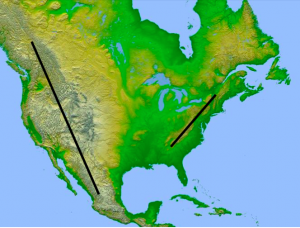

This map shows the location of South Florida’s reef system, which travels all the way down into the Florida Keys. The second image shows Dry Tortugas National Park, TNER is Tortugas North Ecological Reserve, TSER is Tortugas South Ecological Reserve, TBO is Tortugas Bank Open and DRTO is Dry Tortugas National Park. (Ault, 2013)

In addition to coral reefs being ecologically important, they are also economically important. Reefs generate $29.8 billion in global net benefit per year (Chen, 2015). Climate change has caused a decrease in ecotourism, resulting in a decrease in profits from coral reefs. It is estimated that the lost value in terms of global coral reef value could range from $3.95-23.78 billion annually (Chen, 2015). In order for many coastal areas to retain this profit from the reefs, corals must be protected from the harmful effects of climate change.

Florida’s coral reefs are particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change, due to the high population concentration around the coast and the large amount of pollution in coastal waters. Since 1960, Florida’s population has increased by 379% (Ault, 2013). In addition, Southeast Florida is the 8th most densely populated area in the US (Futch, 2011). Increased population leads to increased pollution and runoff, which can be harmful to reef systems. In addition, large infrastructure projects, pipe systems, and beach nourishment can contribute to stresses on corals, all which occur in Florida. The Florida reef system supports the tourism and fishing industries, making it commercially valuable. Without the reef system, Florida would lose two of its largest income generating industries. It is necessary to implant policies that will protect Florida’s reefs from future destruction in order to support the tourism industry as well as to protect the ecosystem.

Another threat facing South Florida’s reefs is from sewage and waste runoff. Due to an increased population, the increased amount of sewage produced is something that the septic systems are not always prepared for. This leads to excess runoff. Water, sponge and coral samples were collected off of the Southeast Florida reef tract and noroviruses were detected in 31% of samples (Futch, 2011). Runoff is particularly dangerous because of wildlife contamination, which has already been observed, but also because excess nutrients in the water cause lead to algal blooms, which can then cause coral bleaching events (Futch, 2011).

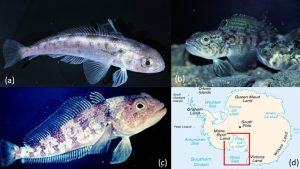

This image show various types of corals as they were placed on reefs in South Florida to test the ability of the reef to recruit new corals to add to its growth. (Woesik, 2014)

Through the use of monitoring systems all throughout South Florida and the Florida Keys, it has been determined that there has been a 44% decline in coral cover since 1996. This shows that there is a dire need to protect Florida’s reef systems. There are various strategies that have been tested to see what works to preserve coral reefs. Often times, management policies are most successful in dealing with marine ecosystems, since they are generally difficult to directly monitor. One such strategy is the use of a marine protected area (MPA). Marine protected areas are generally very successful, and reefs in MPA’s normally show an increase in size, adult abundance and occupancy rates among reef fish (Ault, 2013). This strategy is especially important in Florida because of the large fishing industry. Intensive fishing has diminished top trophic levels, which affects the entire ecosystem’s balance (Ault, 2013). With the main goal of protecting coral reefs, MPA’s also make the entire ecosystem healthier and prevent unsustainable fishing. Environmental policies that limit the number of fish taken from a reef or limit the boating activity in a certain area are very effective at limiting the human disturbances on coral reefs, and can help marine ecosystems recover from anthropogenic disturbances.

In addition, coral recruitment has been used to regrow portions of bleached reefs. This was done in the Florida Keys and Dry Tortugas National Park. However, the results were not promising. Because of already present stressors such as pollution and warm temperatures, most of the corals did not survive once they were deployed on the reef. These results indicate that coral reefs have slow recovery times after bleaching events or environmental stressors (Woesik, 2014).

Coral reefs are vital to the health of the oceans. Without them, many marine species would be critically threatened. It is necessary to protect the reefs that are alive now to ensure their survival in the future. By implementing management policies, it is possible to protect the reefs from further anthropogenic disturbances, and allow them to recover from already-present stressors. If the health of coral reefs in South Florida increase, then Florida will not only benefit economically, but ecologically with improved marine ecosystems.

Works Cited

Ault, J. S., Smith, S. G., Bohnsack, J. A., Luo, J., Zurcher, N., Mcclellan, D. B., . . . Causey, B. (2013). Assessing coral reef fish population and community changes in response to marine reserves in the Dry Tortugas, Florida, USA. Fisheries Research, 144, 28-37. doi:10.1016/j.fishres.2012.10.007

Futch, J. C., Griffin, D. W., Banks, K., & Lipp, E. K. (2011). Evaluation of sewage source and fate on southeast Florida coastal reefs. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 62(11), 2308-2316. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.08.046

Woesik, R. V., Scott, W. J., & Aronson, R. B. (2014). Lost opportunities: Coral recruitment does not translate to reef recovery in the Florida Keys. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 88(1-2), 110-117. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2014.09.017

Chen, P., Chen, C., Chu, L., & Mccarl, B. (2015). Evaluating the economic damage of climate change on global coral reefs. Global Environmental Change, 30, 12-20. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.10.011

Baker, A. C., Glynn, P. W., & Riegl, B. (2008). Climate change and coral reef bleaching: An ecological assessment of long-term impacts, recovery trends and future outlook. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 80(4), 435-471. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2008.09.003