Local taboos could help conserve marine fisheries in Tanzania

By Jess Daly, SRC Intern

In developing nations it is often difficult to effectively enforce marine conservation laws because of a lack of staff and funding. With so little government intervention, it may be unclear to what extent the rules are being followed. A 2017 study by Shalli et al. examined how alternative methods of management might be affecting fisheries in Tanzania.

Specifically, the focus of this project was how traditional knowledge and local taboos alter the behavior of local fisherman. Traditional knowledge is wisdom that is passed down through generations, and taboos are a subcategory that includes the belief that certain actions are either too immoral or too sacred to be done in good conscience. The study examined six different Tanzanian fishing communities (4 rural and 2 urban), and used a wide variety of survey methods to gather information, including observation of fishing practices, a questionnaire given to fishers, and interviews with village leaders.

A fisherman goes out with his boat in the waters off of Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania. [Grant, Milton. “Fishing in Tanzania.” United Nations Photo. 01 May 1991. https://www.flickr.com/photos /un_photo/34848229512]

Those who were given the questionnaire were also asked to provide their ages, genders, education levels, and lengths of residency. Across all of the villages, the majority of fishers were men who were between the ages of 30-40 and had a primary school education or less. However, when asked about local taboos, it was the uneducated elders who were able to provide the most information.

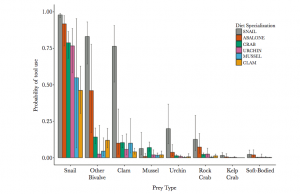

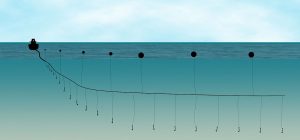

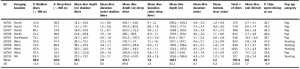

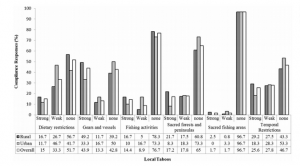

It was discovered that a wide variety of taboos exist within the Tanzanian fishing communities. The first is that certain fish species should not be eaten; reasons given for non-consumption included religious beliefs and fear of toxicity. Specific species and explanations of the taboos varied in the different villages, but all of them discussed dietary restrictions in one way or another. While the trend was present, however, the study found that nearly 50% of respondents did not comply with this taboo. A second class of taboos includes several actions involving the creation and deployment of fishing gear (such as women not touching new nets). These rules were more closely followed, with 44% of respondents claiming that they stringently complied with them, partially because of fear of social backlash. Almost 77% of fishers admitted noncompliance with taboos related to restrictions before or during fishing. More than 97% did not adhere to local taboos that prohibit fishing on certain sacred reefs, and nearly 47% claimed that they fished on certain prohibited days (such as religious holidays).

A graph depicting the levels of compliance to six different “categories” of taboos by different groups of fisherman as either strong, weak, or none. [Shalli et al. https://www.dropbox.com /sh/iyrngyxjy05qhm5/ AACAfkJqi4aOBqumSsEb0cZNa? dl=0&preview=shalli+et+al+2017.pdf]

Many of the local taboos, if they were widely followed, would aid in marine conversation by limiting things like fishing days, target species, fishing in sensitive reef areas, and catch size. While it appears that the majority of taboos are ignored in practice due to growing village populations and an increased demand for fish, it is believed that if local fishermen were educated in how these taboos actually affect population sizes, they would be more likely to observe them. In addition, local conservation laws should be aligned with existing taboos to highlight just how much they could aid in successful fisheries management.

Work Cited

Shalli, Mwanahija Salehe, et all. 2017. The role of local taboos in management of marine fisheries resources in Tanzania. Marine Policy 85: 71-78.