Propeller Scars in Seagrass Beds: Recovery and Management in the Chesapeake Bay

By Grant Voirol, SRC intern

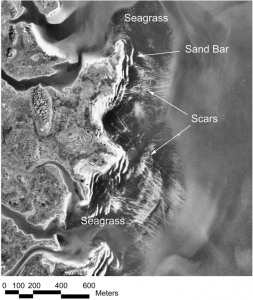

Seagrass beds may seem simple on the surface, but they provide a wide variety of ecosystem services ranging the biotic and abiotic, economical and ecological. Most importantly, seagrass beds protect against coastal erosion, recycle vital nutrients, and provide habitat and food for essential species for the ecosystem and for fisheries (Barbier et al. 2011). However, due to their proximity to cities and human development, these unsung heroes are often subjected to fragmentation via propeller scarring. Seagrasses occur in relatively shallow waters, and when boats and other vessels operate in these shallow depths, their propellers can grind up the sandy substrate and rip up the seagrass. This leaves a visible “scar” through the habitat (Figure 1).

Aerial photography of Browns Bay in the Chesapeake Bay (Orth et al. 2017).

In a recent paper, Orth et al. 2017 utilized the Chesapeake Bay submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) monitoring effort through the Virginia Institute of Marine Science to assess the degree of propeller scar damage present in the Chesapeake Bay and the impact of management decisions. This allowed these researchers to examine over 25 years of aerial photography. Most studies on propeller scars in seagrass beds can only monitor for a few months to a few years, but this multi-decade effort can examine the more long-term effects of specific anthropogenic stressors as well as recovery potential. In order to measure these qualities, researchers counted the number of new scars each year as well as the length of the scars. Additionally, preliminary results allowed for the development and implementation of management strategies that can also be observed and tested for efficacy.

The researchers found that on average during the entire study period, 112 new propeller scars were found in the Chesapeake Bay each year and that the average length of each new scar was 78.5 meters long. The time required for a propeller scar to become fully vegetated again was variable. The average was about 3 years, but the range ran from 2 to 18 years in order to recover. This shows that the Chesapeake Bay has been subjected to high levels of propeller scarring over the past few decades. The study examined the fishing industry, recreational boats, and moorings and docks as potential causes of these scarring events and concluded that the main anthropogenic sources are the fishing practices of crab scraping and haul seining. Crab scraping is when boats drag metal baskets through the seagrass beds in order to harvest molting blue crabs. Surprisingly, the physical action of the basket is not the cause of the scars, but when the net on the basket gets clogged with stray pieces of seagrass, the boat must increase its power in order to continue pulling the basket through the bed. This increase is the true cause of the uprooted seagrass. Causing more damage than crab scraping is haul seining, which is where multiple boats pull nets of up to 600 meters through the seagrass beds to harvest fish. The pulling of these nets, as well as the withdrawal of the boats carrying loads of fish, causes long scars throughout the beds.

To combat these stressors on the seagrass beds, scientists, government officials, and commercial groups held meetings to discuss the issues and possible options. The commission developed a strategy that focused on the more harmful of the two practices: haul seining. The main regulations were to limit the length of nets used, prohibit the use of two boats to drag nets, limit the distance a boat could drag a net, and requiring fishermen to report where they will fish during the following 24 hours.

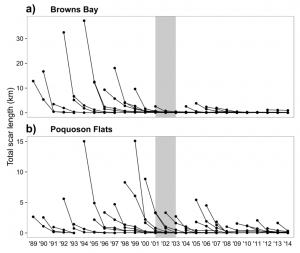

Two highly damaged areas of the Chesapeake Bay were monitored in order to see the effects of these new regulations. Following implementation, Browns Bay showed a significant 90% reduction in the number of new propeller scars and an 89% reduction in total length of all scars. Poquoson Flats had a 43% reduction in the number of new scars found. While this reduction in number of scar was not statistically significant, the total length of all scars in Poquoson Flats did show a significant reduction by 57% (Figure 2).

Total scar length of both a) Browns Bay and b) Poquoson Flats. Gray shaded area represents years of development and implementation of haul seining management plan (Orth et al. 2017).

Luckily for the Chesapeake Bay, a swift and scientifically based management plan could be employed that resulted in substantial improvements for the native seagrass beds. In this case, fishing activity was the main contributor to propeller scarring and not other sources. However, this is not always true. In other areas, such as the coasts of Florida and Texas, propeller scars are more often caused by recreational boat traffic, meaning that new management tactics are needed (Zieman 1976, Dunton and Schonberg 2002). Dunton and Schonberg identify the most likely cause of recreational boat damage as accidents by boaters misjudging water depth, boaters utilizing “shortcuts” through the seagrass beds, and general ignorance of the beds’ importance. In this case the best steps to move forward would be to educate the public on the importance of these communities and the harm that they may be causing as well as additional marking of channels or construction of a single channel so as to keep boat traffic confined to a single path instead of spread throughout the beds. In this way, we can keep this important ecosystem healthy and free of harmful “scar tissue”.

Works Cited

Barbier, EB, Hacker SD, Kennedy C, Koch EW, Stier AC, and Silliman BR. 2011. The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecological Monographs 81: 169–193.

Dunton KH, and Schonberg SV. 2002. Assessment of propeller scarring in seagrass beds on the south Texas Coast. Journal of Coastal Research SI 37: 100–110.

Orth RJ, Lefchek JS, Wilcox DJ. 2017. Boat Propeller Scarring of Seagrass Beds in Lower Chesapeake Bay, USA: Patterns, Causes, Recovery, and Management. Estuaries and Coasts 40(6):1666-1676.

Zieman, J.C. 1976. The ecological effects of physical damage from motor boats on turtle grass beds in southern Florida. Aquatic Botany 2: 127–139.